A critical property of turbine oil is its ability to separate from water, known as its demulsibility characteristic. This property is essential for protecting turbine components from inadvertent damage to viscosity changes or corrosion. Water and oil are immiscible due to their distinct chemical natures.

The principle “like dissolves like” explains this phenomenon: water molecules are polar, possessing an electronegative oxygen atom and electropositive hydrogen atoms, while oil molecules are non-polar, lacking strongly electronegative or electropositive atoms.

Oil and water don’t mix – unless demulsibility fails.

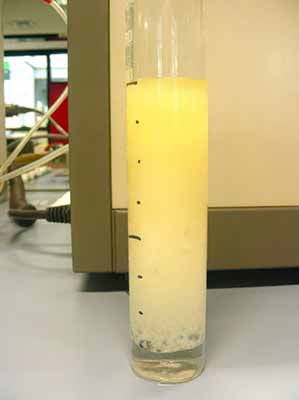

When mixed, water molecules tend to agglomerate rather than mix with the organic hydrocarbon molecules, causing water to be rejected from the oil. Oil floats on water because its molecules are larger and significantly less dense. However, when an oil loses its demulsibility characteristics, a cloudy emulsion is formed, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A sample of highly emulsified oil at the conclusion of a demulsibility test. Courtesy of Siemens Energy.

Measuring Demulsibility Using ASTM D1401 (ISO 6614)

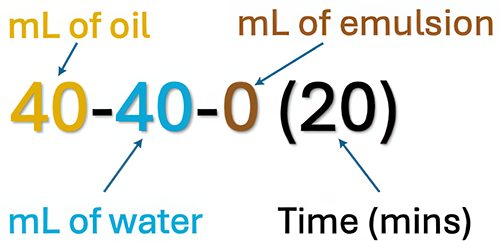

The ASTM D1401 test method is widely used to evaluate an oil’s demulsibility. In this procedure, a 40 mL sample of the oil is mixed with 40 mL of distilled water (or synthetic seawater) in a graduated cylinder. The mixture is stirred for 5 minutes at 54°C. For oils with a viscosity greater than 90 cSt at 40°C, the test can also be conducted at 82°C. An example of the graduated cylinder at the conclusion of the demulsibility test can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Graduated cylinder at the conclusion of a demulsibility test showing the oil and water separated by a layer of emulsion.

The separation time of the emulsion is recorded at specified intervals, typically every 5 minutes, or at a predetermined time limit. If complete separation or reduction of the emulsion to 3 mL or less does not occur within 30 minutes (or another specified time limit), the volumes of oil, water, and emulsion remaining are documented.

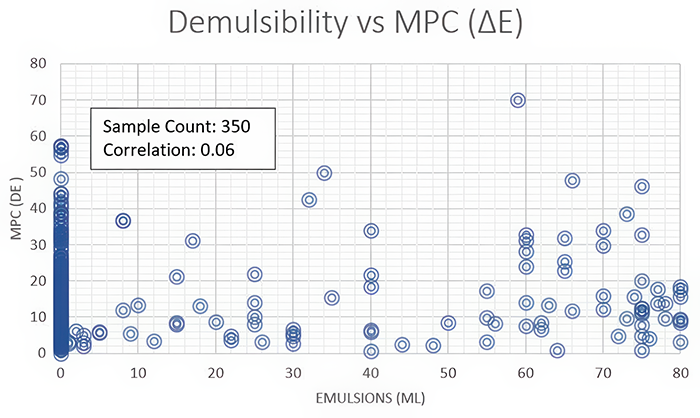

For instance, a result of 40-40-0 (20) indicates that after 20 minutes, complete separation was achieved, resulting in 40 mL of oil, 40 mL of water, and 0 mL of emulsion. This can be seen in Figure. 3.

Figure 3: Interpretation of demulsibility results

Factors Leading to Poor Demulsibility Performance

Turbine oils can dissolve small amounts of water, referred to as dissolved water, typically holding about 100-150 ppm at room temperature. The presence of polar-heteroatom hydrocarbon species in the oil significantly impacts water separability. In-service turbine oils may fail demulsibility tests due to polar constituents, allowing water to become miscible in the oil.

Even minimal amounts of polar molecules can severely affect demulsibility, depending on their polarity and chemistry. For instance, a laboratory study by ExxonMobil indicated that calcium levels as low as 3 ppm, in the form of calcium alkylbenzene sulfonate, can impact demulsibility values.

Field tests have shown that even smaller concentrations can be problematic, making identifying the root cause of demulsibility failure challenging. Occasionally, oil analysis can pinpoint a root cause, such as the presence of calcium. However, in most cases, the material present is too minimal to be identified through conventional analysis methods like FTIR or ICP spectroscopy.

Polar constituents enter turbine oil either through fluid contamination or fluid degradation.

Fluid Contamination

Contaminants can enter the turbine oil system through various means:

- Oil top-offs, introducing contaminants and new additive chemistries

- Maintenance activities, such as flushing, which introduce detergents or cleaners

- Air ingression, carrying contaminants into the fluid

- Water and steam leaks, polluting the oil with water and its treatment chemistries

Alkylbenzene sulfonate detergents are common contaminants that may remain in the turbine oil system after a flush. This chemistry adheres to metal parts during cleaning, making it difficult to remove and destroy demulsibility at very low concentrations. The molecule’s structure, with a strongly polar sulfonate head and a non-polar alkyl-benzene tail, allows it to combine water and oil phases. Higher component concentrations result in poorer demulsibility.

Even trace contaminants can destroy oil’s ability to shed water.

Steam turbines are prone to seal leaks and moisture ingress. While the ingress of high-purity water can lead to various performance issues, it does not directly affect demulsibility characteristics. However, the water is treated with corrosion-preventing chemicals such as boric acid, lithium hydroxide, and hydrazine.

Chemicals like sulfite are added to eliminate dissolved oxygen, and phosphate compounds are used to control pH and prevent scale formation. These polar chemicals can adversely impact the demulsibility characteristics of turbine oil.

Fluid Compatibility

Fluid compatibility is measured by the interaction of fluid components. Antagonistic interactions first affect interfaces—air/fluid (foam), solid/fluid (MPC or haze), and water/fluid (demulsibility). Factors affecting compatibility include fluid mixing, improper flushing, and formulation changes, which alter the fluid’s polarity and surface polarity.

Increased fluid polarity enhances the interaction between polar water molecules and the fluid, affecting demulsibility. Ingress chemistries with polar-head/hydrocarbon-tail functionality or internal polarity can similarly impact fluid polarity.

Fluid Degradation

Thermal and oxidative stress on turbine oils produce degradation products, known as soft contaminants, which are polar and can be measured by the MPC test (ASTM D7843). Oil degradation is commonly believed to be the primary reason for diminishing demulsibility characteristics.

This makes logical sense since degradation products are polar, and the introduction of polar constituents to the oil causes demulsibility characteristics to fail. However, in practice, this relationship may not be accurate. We analyzed the data from 350 used turbine oil samples to measure the correlation between the mL of emulsion from D1401 and the DE value from D7843, as seen in Figure 4.

Demulsibility failures are often caused by contamination—not degradation.

The correlation between MPC and emulsions was 0.06. If there were a perfect correlation, this value would be 1, or if there was a perfect inverse correlation, -1. A value of 0.06 means there is no correlation whatsoever.

Figure 4: A correlation study between demulsibility (emulsion layer) and MPC value illustrates no direct correlation between oil degradation and failing demulsibility.

Addressing Failing Demulsibility in Turbine Oils

When evaluating oil analysis results, the most critical step is taking appropriate action. Common questions that arise include:

- What corrective action is required based on these results, if any?

- Is there any indication of a sampling error or lab error?

- Should I adjust my sampling intervals based on these results?

- What are the implications of not taking action?

According to ASTM D4378 (Standard Practice for In-Service Monitoring of Mineral Turbine Oils for Steam, Gas, and Combined Cycle Turbines), action is recommended when there are ≥3 mL of stable emulsion after the demulsibility test. The guideline suggests several actions:

- Identify and eliminate the source of contaminants.

- Clean the system using adequate filtration techniques.

- Consider an oil change if water separability cannot be restored.

However, making an informed decision involves more than just following these guidelines; operational risk must always be considered.

There are numerous instances where turbine oil is replaced due to failing demulsibility, despite all other parameters being within acceptable limits. Often, the new oil also fails demulsibility shortly after the change, leading to unnecessary expenditure of resources.

Turbine oils can fail demulsibility tests and still perform reliably for years.

Poor demulsibility properties in turbine oil do not inherently indicate an operational risk. Turbine oils can still deliver excellent performance for years, even with failing demulsibility values. The risk arises only when water enters the oil, potentially affecting its viscosity and separation properties.

Even then, failing demulsibility may not pose an additional risk to the turbine. For gas turbines, water ingress is rare and typically evaporates quickly. For steam turbines, effective water removal can mitigate operational risks.

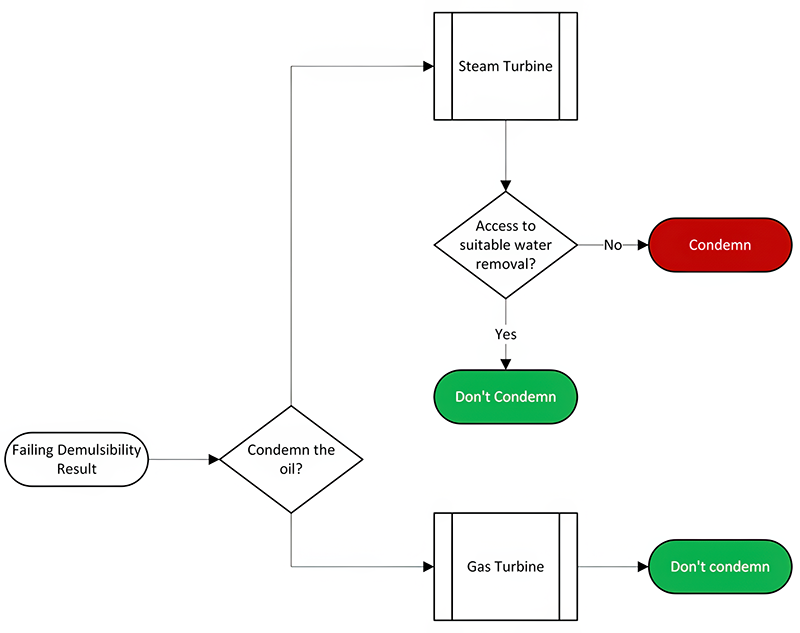

Failing demulsibility should be considered a condemning criterion if the application is prone to water ingression and there are no suitable water removal technologies available. The flow chart in Figure 5 illustrates this decision-making process.

Figure 5: Decision making process to determine if an oil should be condemned based on failing demulsibility characteristics

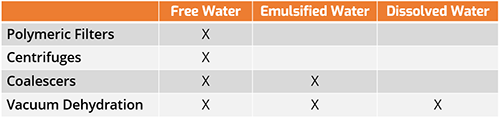

To ensure the effective removal of water from turbine oil with compromised demulsibility, it is crucial to employ advanced water removal technologies. Specifically, the utilization of a modern coalescer or vacuum dehydration system is recommended. Older methods, such as centrifuges or polymeric filters, are inadequate for eliminating dissolved or emulsified water, as demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1: Effectiveness of various water removal technologies on the three phases of water

Like with any oil analysis test slate, the data point from one test data cannot be viewed in isolation. If turbine oil demulsibility is poor, viewing other oil analysis data may help determine the reason why. Additional testing will help you to better assess the overall condition of the fluid allowing more informed decisions.

In conclusion, the demulsibility characteristic of oils is a critical factor in maintaining the operational integrity and longevity of turbine systems. The ability of turbine oil to separate from water is essential for preventing viscosity changes and corrosion, which can lead to significant damage and operational risk.

Poor demulsibility does not inherently indicate an operational risk, but it becomes a concern when water ingress is likely and suitable water removal technologies are not available. By employing modern water removal techniques, like vacuum dehydration, and understanding the factors affecting demulsibility, operators can make informed decisions to ensure the reliability and performance of their turbine systems.