I recall starting my career in the mines in the late 1980s when Health and Safety was beginning to become a huge priority. I remember the sign at the entrance with the target and actual hours worked without incident.

Since then, whatever the industry, every site visit I’ve undertaken is usually only possible following a site induction, and having worked off-shore extensively over the last twenty years, I have regularly had to update my Basic Off-shore Survival Induction and Evacuation Training (BOSIET) along with the Helicopter Underwater Evacuation Training (HUET).

Safety is so integral in any business now that systems such as “Stop the Job” and similar systems requiring employees to complete two Observation cards per week are commonplace, especially in the oil and gas sector.

Safety comes first, followed by the environment and then profits, and no one will ever lose their job because of stopping work where safety is at risk.

Over the years, though, safety has become the norm, from simply slipping on a seat belt to automatically reaching for the safety glasses when I’m tinkering in the garage. It’s become second nature to the extent that I recall once stepping out of the office on a site and, within a few paces, feeling something wasn’t right: I’d forgotten my hard hat on the peg.

The culture of safety has become ingrained, with few willing to risk the shortcut of not preparing for a job. There is no excuse for not taking the necessary precautions when working.

Signage is a constant reminder, colleagues are a constant reminder, legislation is the final word; safety must always be complied with, no matter how low the risk.

There’s a sign I often see on the mirrors in the washrooms on sites; “Who’s responsible for your safety?”. What if there was another that said, “Who’s responsible for reliability on this site?”

Sadly, reliability does not enjoy the same legislation as Health and Safety or the environment. Therefore, it is too easy for senior management to overlook reliability and spend the money only where legislation requires, that is, safety and the environment.

Yet, reliability is a fundamental aspect of improving health and safety and reducing environmental impact. However, for this article, I will focus on safety and how reliability and lubrication best practices can help.

Fundamentally, planned work is always safer than reactive work.

Reactive work is typically:

- “At risk” work requiring permits for:

- Hot work

- Working at height

- Confined spaces entry

- More involved and undertaken less frequently than planned work with little time to assess the risks properly.

- Accompanied by management pressure to restart the system as soon as possible with the attendant risk of shortcuts being taken and even encouraged.

Planned work is proactive and typically:

- Undertaken routinely so the risks are understood.

- More straightforward work involving inspections and minor adjustments to the system.

- Time is allocated accordingly to complete the job safely.

Data from the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA), an agency of the U.S. Department of Labor, showed that 43% of injuries and 24% of fatal accidents in mining occur during conveyor maintenance or inspection.

The conveyor-related fatal accidents typically include replacing idlers, clearing blockages, and cleaning up with a shovel or hose. However, an aspect of conveyors is that the work is often at height.

Consequently, any lubrication-related reliability issues will increase the risk of injury or fatality.

Notably, Ron Moore, managing partner of The RM Group, Inc., wrote an article, “A Reliable Plant is a Safe Plant is a Cost-Effective Plant,” published by Life Cycle Engineering and available on their website. Please look for this paper on the internet and read it.

However, in the concluding summary, Ron Moore wrote:

Finally, anyone who has been through a safety initiative understands that to improve safety, you must go through a series of specific steps to drive the improvement process. These are listed below.

- Top-down leadership – clear, consistent expectations

- Bottom-up ownership and employee engagement

- Education and training

- Action plans and measures

- Visual communication of expectations

- Standards and procedures

- Benchmarking and aggressive goals

- Audits and assessments

- Root cause focus

- Rewards (& willingness to challenge non-compliance)

- Resources for supporting improvement

- Continuous improvement expectations and process

- A culture – a way of life

All the companies I’ve worked with have policies and strategies similar to those related to safety. Few companies have these policies as it relates to reliability. Moreover, if the CEOs of these companies truly believe that safety is a top priority, they must have similar policies for reliability. The truth is they do not. They must, or else their commitment to safety is weak.

As I look at this list in the summary above, I see all the parallels with introducing a lubrication best practices program. Each of the above-bulleted points is what we need to implement a world-class lubrication management system successfully. The final sentence, “They must, or else their commitment to safety is weak.” speaks volumes.

So, what aspects of implementing a lubrication best-practices strategy and its implementation help address and improve safety? In fact, should not reliability engineers be putting safety as the main driver for justifying changes over the cost benefits? Let’s look at a few areas that I see as potential safety enhancers.

Desiccant Breathers

The key aim of a desiccant breather is to minimize both moisture and fine particulate ingress. However, they can also reduce oil vapors exiting the machine.

This has several safety benefits:

- Minimizes poor air quality for personnel working in the area.

- minimizes oil vapors settling on walkways and creating a slip hazard.

- Indicates high humidity in the system, creating an early warning of problems and possibly avoiding catastrophic failure.

Quick-Connects

This one is my favorite, having observed funnels and open jugs left next to machines on so many occasions. The use of quick-connectors for attaching a hose to pump the oil into or out of a machine will not only eliminate the risk of contamination associated with pouring oil through a funnel but, from a safety perspective, it will:

- Minimize the risk of spillage and necessary clean-up.

- Minimize the risk of back injury associated with lifting large containers to pour oil through a funnel.

Moreover, it follows the fundamental principle of implementing reliability: “Make the right thing to do the easy thing to do” and encourages best-practice adoption.

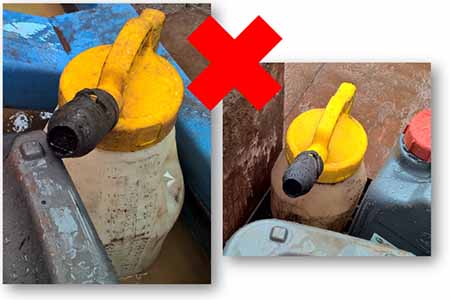

Sealable Oil Containers

While these have now been available for over twenty-five years, I still find these containers left wide open. In the image below, these containers were allowing rainwater into the containers simply because the spouts were not being closed, creating a reliability issue and a potential injury because of water-induced wear and failure on the asset.

However, the simplicity of the design means that with the spout closed, spillages are avoided when the container is dropped or knocked over. I always prefer using the hand-pump version and quick-connectors on the hose and machine mentioned above to eliminate the risk of spillages and the possibility of the spout being left open.

Easily Accessible Inspection Devices

Too often, I find that oil-level sight gauges are inaccessible or awkward to reach. Apart from the obvious issue of potential catastrophic failures resulting from not inspecting levels properly and missing other warning signs, the very nature of awkwardly placed inspection units puts personnel at risk because of having to lean over equipment, for example.

Ensuring the 3D inspection units and bearing oil sight glasses are easy to see without reaching and not in dark places will help reduce risks.

Storage

This is a whole area for safety that must be addressed concerning safe storage.

Up-to-date Safety Data Sheets SDS are important as printed copies in the oil store, along with the appropriate provision of PPE (Personnel Protective Equipment) and fire-fighting aids.

However, correct lifting equipment is essential. About twenty years ago or more, I noted a lot of sites transitioning away from larger containers, such as 208L drums, to the smaller 25L pails.

While lifting a 25L pail is safer, back injury is a potential issue without the proper training on correct lifting. Add to this that the cost per liter of a smaller container increases, so there is a tendency to buy larger drums and IBCs (Intermediate Bulk Containers) to reduce the purchase price.

Still, the proper rigging and the correct provision of the bunding for the standing of these is critical.

Hence, using storage tank systems to dispense smaller containers is becoming increasingly popular. While the initial cost is high, the long-term benefit is providing filtered oil from correctly color-coded tanks and dispensing points. This means smaller containers can be used while still enjoying the cost savings of the larger drums.

Providing a dedicated storage unit for satellite lubrication activities at points around the plant makes a lot of sense, especially as these are portable and can be moved should the need arise. However, the units offer a best-practice set-up with rapid implementation.

Lustor System

Safety with Greasing

As a good friend, Haris Trobradović often states in his lectures, we call it a grease gun because it can kill. Not just machines but people, too. I always recommend that the flexible hose on a grease gun should be replaced annually.

This incident was reported in December 2013 at Liebherr Australia Pty Ltd. The operator was attempting to remove a hand-operated grease gun from a grease nipple after pumping several times to try to clear a blocked grease nipple or Zerk.

While gripping the hose and maneuvering it to release the nozzle, the hose ruptured, injecting grease into the operator’s little finger. It should be noted gloves were not being used at the time.

Medical attention was sought, resulting in a lengthy operation and removal of a vein in the forearm, which was replaced with an artificial vein.

In conclusion, I hope the above discussion has provided an alternative view on reliability. When seeking to implement the improvements, it is not just about the system’s reliability but the safety of those who maintain and operate the systems.

Never underestimate the safety implications when justifying the upgrades, nor should one underestimate the potential hazards for something as simple as a lubrication tool, even though so many see lubrication as a simplistic discipline for unskilled workers.