What’s the Right Number of Lubricants for Your Plant?

Over the years, I have been to sites with either too many or too few lubricant types.

Both scenarios are potentially costly.

On the one hand, too many types of lubricant are costly in terms of purchase price and ultimately risk downtime due to the wrong lubricant being used.

On the other hand, too few lubricant types are costing the company due to overzealous consolidation, leading to a possible substandard lubricant specification in use.

Why Do Lubricant Inventories Get Out of Hand?

Generally, I find that where too many lubricant types exist, usually differing brands, is the result of procurement blindly following the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) insistence on a brand for “Warranty reasons”. Legally, the OEM should provide a recommended lubricant specification and include a list of brands. However, if a non-recommended brand can be shown to meet or exceed the required specification, the warranty issue is no longer a concern, especially if the OEM is contacted and obtains written approval.

I have been through this process on several occasions, especially on new builds, where various electric motor and pump suppliers will try to enforce a particular brand, sometimes for commercial rather than technical reasons.

Where too many lubricant types exist, usually differing brands, is the result of procurement blindly following the OEM insistence on a brand for warranty reasons.

Another possibility is that the procurement team is shopping around for the best pricing, resulting in numerous brands in the storeroom. This has happened in both small, family-run businesses and in larger operations where a procurement contractor is responsible and is shopping for the best deal.

What Makes Lubricant Consolidation Worth the Effort?

Primarily, the main reason is cost-benefit.

Purchasing fewer lubricant types means each remaining type in use is purchased in greater volumes, thereby realizing potential cost savings through negotiated discounts for higher volumes.

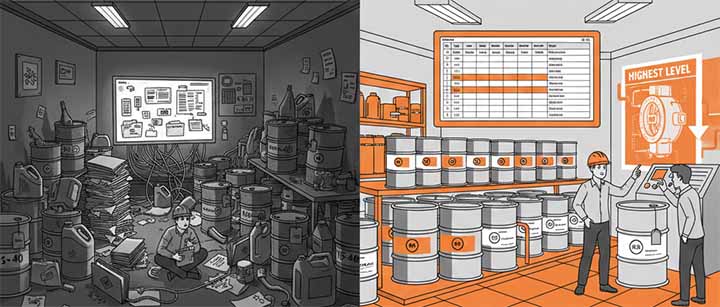

This goes further: particularly with oils, these can be bought in larger container sizes, further reducing the purchase price, as typically the larger the container, the cheaper the unit cost. However, while handling small pails is cheap, handling drums is more complex. Still, with the installation of a “best practice” bulk storage system, the oil can be purchased in drums but handled and transferred via smaller, more easily managed, sealable, and refillable containers that also meet “best practice” guidelines.

A secondary cost reason is the reduced risk of using the wrong lubricant and the resulting damage from cross-contamination.

This latter issue, however, is also the result of a lack of “best practice” with no tagging of the machines and no internal company policy of colour-coding the lubricants, either, allied to poorly written work orders that lack detail.

Is There a Business Case for Consolidation?

Yes…and no.

Be careful of being penny-wise and pound-foolish, as we say in the UK, or should that be cents-wise and dollars-foolish?

Let’s clarify. In the late 1990s, working with BP, they stated that the average customer will spend less than 1% of their annual maintenance budget buying lubricants, but will spend more than 40% of it dealing with the outcomes of poor lubrication practices on site.

To put that into context, with a $10 million annual maintenance budget, less than $100,000 is spent on lubricants, while $4 million is spent on repairs, rebuilds, and other downtime costs associated with poor lubrication management.

So, would you rather chase a $20,000 savings or deal with an internal issue costing $4 million and recover at least $1 million of that?

The average customer will spend less than 1% of their annual maintenance budget buying lubricants, but will spend more than 40% of it dealing with the outcomes of poor lubrication practices.

In my opinion, the cost-benefit of a lubricant consolidation exercise will also depend on the industry type. In some instances, certain industries, such as Food & Beverage and Pharma, have limited lubricant ranges, with consolidation already underway, particularly for NSF-approved Food-Grade lubricants, and limited asset types.

On the other hand, Oil & Gas, mining, Pulp & Paper, for example, not only have a larger range of lubricants to suit a wide variety of asset types, but these industries will also utilise greater quantities, especially in fluid power systems, engines, transmissions, and turbine trains for compressors or power generation.

The Right Way to Consolidate Your Lubricant Program

Lubricant consolidation, in my opinion, is again an essential first step in implementing a world-class lubrication management programme. Apart from getting a handle on all the lubricants on site, it will help identify obsolete stock, address issues arising from product name changes, and create a plan for the discontinued and hard-to-obtain products still on the list.

Ideally, using internal or sub-contracted, independent expertise, a list of the lubricants in use should be compiled at the beginning. This is a useful exercise, as I often find multiple duplicates in Enterprise Resource Planning systems (SAP, Maximo, etc.) for lubricant accounting codes. While each container size of a lubricant type should have its own accounting code, there are often instances where procurement has inadvertently added another, but under a slightly different term, for example, as 15-40 instead of the original 15W-40.

Once the duplicates have been removed, the list should be tabulated in a spreadsheet with columns denoting the brand, product, and then further itemized by column headings not only for the base oil type, thickener type, and intended application, but also relevant to the lubricant type, showing the physical, chemical, and performance properties.

I would then prioritise the lubricants, with the highest priority given to those used in critical assets or specialised equipment that must remain, and the lowest to those in general applications and low-criticality assets.

However, be aware that, for greases. At the same time, it is tempting to use a multi-purpose grease for the motors; the base oil’s viscosity may be too high compared to a specialist electric motor bearing grease, which can increase power consumption.

In addition, gearboxes and transmissions need investigation, as Sulphur-Phosphorus-based Extreme Pressure oils may not suit all designs. In fact, apart from the chemical issue with the S_P EP oils, which require a solid-suspension type physical EP oil, some gears may only need an Anti-Wear oil.

Rather than dumbing down to the cheapest level, take the opportunity to raise the bar to the highest level.

A final comment here is that rather than dumbing down to the cheapest level, take the opportunity to raise the bar to the highest level. For example, switching from mineral to synthetic base oils may seem counterintuitive in terms of cost; however, there are several benefits. The higher VI of the synthetic base oils may help consolidate into different Viscosity Grade oils, while potential cost benefits include longer oil change intervals and reduced energy consumption.

What Comes After Consolidation?

While the consolidation may be your only objective, the cost-benefit of such a process will be limited and, in fact, incur additional costs due to downtime resulting from uncertainty about the new lubricant range and cross-contamination.

In addition, it is simply not possible to start topping up with a revised oil grade, such as an ISO VG 22 synthetic oil, on a gearbox currently using an ISO VG 320 mineral oil. Hence, the likelihood is that the consolidation won’t happen.

Further, even if consolidation reduces the number of lubricant types in use, it may still result in a variety of container sizes or require purchasing smaller containers at a higher unit cost unless steps are taken to address processing with larger containers in the lubricant store.

Simply put, the real benefit comes from a structured process of improvement across the whole lubrication management strategy.

Should You Let Your Supplier Run the Consolidation?

It is, of course, possible, and increasingly, lubricant vendors are going down this road with their clients. A strong supplier with your best interests as the end user at heart is the ideal approach. Unfortunately, I have seen too many instances of a cursory review of the lubricants resulting in over-consolidation to the detriment of the machinery.

One outcome of creating a spreadsheet, as mentioned earlier, is the generation of an internal lubricant specification document. With actual product names removed, the folder of specifications for each lubricant can be shared with all suppliers as part of a single-source procurement process. This means that, without the current product name, the lubricant supplier must review the specification document in detail, note its properties and performance criteria, and recommend a suitable lubricant.

What Are the Benefits of a Single Lubricant Supplier?

Just as there is a cost-benefit to lubricant consolidation, rationalising the supplier base can also realise cost savings. Buying all the lubricants from one source will also help push for discounts beloved of bulk purchasing.

There are other benefits to single sourcing, too. When evaluating responses to the tendering process, a single-source supplier is more likely to support the process once in place. Naturally, this depends on the volume of business, but a single-source supplier is more likely to commit to your process of improving the lubrication management strategy.

With actual product names removed, the folder of specifications for each lubricant can be shared with all suppliers as part of a single-source procurement process.

Of course, a single-source supplier may not be able to cover all lubricants, so some allowance will need to be made for specialist lubricants.

What’s the Big Picture Here?

While a cost-benefit, the desire for lubricant consolidation should not be driven by procurement looking to maximise short-term savings, especially by avoiding the temptation to err on the side of cheaper, lower-performing products.

Lubricant consolidation should be driven by reliability professionals looking to improve the overall lubrication strategy, in which knowledge of future improvements in storage and handling will enable more effective consolidation decisions, maximising the cost-benefit.