The online resource Dictionary.com defines the word “clean” as “free from dirt” and “free from foreign and extraneous matter.” To most, “clean” is a subjective term, the interpretation of which depends on the subject matter and the interpreter’s standards for “clean.”

For example, when they were asked to clean their rooms, my teenage boys had a much lower standard and interpretation of “clean” than I did. To be effective and repeatable, cleanliness standards must adhere to a tangible set of measurable parameters.

Oil cleanliness is universally measured using the ISO 4406:1999 cleanliness-code rating system explicitly designed for lubricating oils.

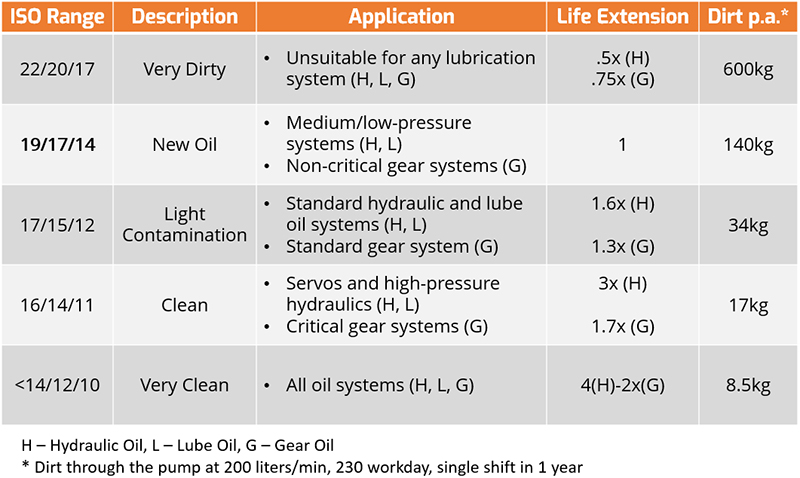

Through this rating system, a user knowing the number of contaminant particles greater than 4, 6, and 14 microns in size that are present in a 1-ml lubricant sample (determined by oil analysis) can cross-reference them against a pre-determined particle-concentration range and come up with an ISO-range number value.

For example, a 19/17/14 lubricant sample value (typical of new oil) translates to the presence of 2500 to 5000 particles >4 microns in size, 640 to 1300 particles >6 microns in size, and 80 to 160 particles >14 microns in size present in the 1-ml oil sample.

Understanding that a full-film hydrodynamic separation of two moving surfaces is only 4 microns thick, using new oil without pre-filtering to a cleaner state would result in surface finish damage and wear from the onset of use.

When new or virgin stock oil is received from the supplier, many maintainers mistakenly believe they are receiving a “ready-to-use” product.

This is not always the case, as depicted in Table 1. It shows new oil is generally received with an approximate cleanliness level of 19/17/14 ISO, which may only be suitable for non-critical gear systems.

Using 19/17/14 oil in a recirculating system can pass the equivalent of 140 kilos (over 300 lbs) of dirt through the pump annually.

Table 1. ISO 4406:1999 Solid Contamination Code Suitability Matrix

Most oil-lubrication applications require the oil to be cleaned and polished by passing it through a filtration system before use in service. We can see in Table 1 that “In service” oil dirtier than 19/17/14 is unsuitable for any lubrication or hydraulic system and will require replacement or cleaning using a kidney loop set up with a portable filter cart.

Once a machine is in service, lubricants will need to be changed regularly, and if improved cleanliness levels are to be achieved, a portable filtration transfer system will be required.

A portable filter cart is one of the most efficient and practical tools available to ensure lubricant cleanliness. These carts are designed to filter and polish oil clean as it is transferred from a bulk delivery tank into a machine reservoir.

Alternatively, the filter cart can recondition and clean up machine reservoir oil while in service, connected to the reservoir in a “kidney-loop” style setup. Should minor water problems exist, specialized absorption filters can be used to extract any free and emulsified water present in the oil.

The primary function of any filter cart is to filter fluids. A typical design employs a two-stage (coarse/fine) filtration process in which a gear pump(s) moves the oil through the filters under pressure.

The inlet, or suction side, is the first-stage, low-pressure side that captures larger contaminant particles (above 150 microns in size). The oil is then pumped through the (coarse) inlet filter to the second-stage, high-pressure outlet, or delivery side (fine) filter designed to capture much smaller particulate matter that can be filtered to less than 5 microns in size, depending on the filter rating used.

Achieving Your Oil Cleanliness Levels

The number of passes through the filter cart to achieve the appropriate cleanliness level will depend on the “start” and “finish” cleanliness levels, filter types, and filter ratings. Oil analysis will be required to establish cleanliness levels.

Choosing a suitable combination of pump and filter size/type will require consultation with the filter-cart manufacturer, which will need to understand your working particular environment and the type/viscosity of oil(s) you use.

The cleanup rate (speed) will depend on the reservoir size, pump flow rate, and the cleanliness-rating delta. What can be measured immediately is the time to perform one complete filter pass through the filter cart, which is calculated using the following formula:

(Reservoir Size x7) / Filter Cart Flow Rate = Time for a Total Single-Pass Filtration

60 gal x 7 / 10gpm = 42 minutes for a total single-pass filtration

(i.e. 1 x filtration of reservoir capacity)

If the plant lubricants are consolidated, and cleanliness levels are known, a matrix can be developed to determine how many passes are required to achieve an acceptable cleanliness level in each reservoir.

Filter-Cart Best Practices

To eliminate cross-contamination of lubricants, multiple filter carts must be employed. Dedicate and tag each filter cart to one lubricant for transfer and cleaning. Pilot the filter cart program with the site’s most critical and/or most utilized lubricant type.

- Pre-determine the cleanliness rating for each gearbox and reservoir and mark on both the reservoir and the PM checklist.

- Always clean the unit after each successful transfer operation, paying particular attention to open wand ends and open drip trays under the filters and pump area. Open oil is a dirt attractant and can be transferred unwittingly if the cart and its components are not kept scrupulously clean. TIP: Once cleaned, wrap the wand(s) and open cavity of the drip tray with film wrap similar to that used for wrapping and protecting food items.

- Unless specified, most filter carts are sold with open-end transfer wands fitted to the delivery- and suction-hose ends. These wands are designed to slide easily into the reservoir openings of the donor and recipient reservoirs. In a program designed to filter contaminants from the oil, this type of delivery fitting can allow moisture and dirt contamination into the respective reservoirs during the transfer process. To combat that problem and ensure a contamination-free transfer process, fit the filter-cart delivery/return hose ends and reservoir fill/drain ports with “quick-lock” style couplings. As the reservoir will be airtight, it must also be fitted with a quality desiccant-style breather and, in the case of larger-capacity reservoirs, a closed-loop expansion tank.

- Specify “kink-resistant” flexible suction and delivery hose to prevent pump cavitation. Clear hoses allow a visual reference of the oil flowing through the lines.

- A filter cart’s electric motor requires access to electricity. Ensure an electrical outlet is within easy reach of the unit’s electrical cord. If the cord is short, consider mounting a retractable cord caddy on the cart and verify it is long enough to reach all necessary outlets.

- Paint a lined box shape, similar to a lay-down area, as close as possible to the oil reservoirs that will be serviced. This will allow filter carts to be positioned for quick, unobstructed use within reach of the necessary hose and wand assemblies.

- Place all filter carts on a “before usage” checklist routine to ensure their filters do not go into bypass mode from being too dirty.

A portable filter cart can play an essential role in any lubrication-management program, and for good reason. Not only do these multi-tasking workhorses deliver oil at the right cleanliness level, but they also can perform transfer and oil cleanup while machines are running. How much is that worth to your operations?

This article was originally published in The Ram Review.